BEYOND ZEROThe literary world just wasn't ready for Gabriel Krauze's first novel. Will they have the stomach for his second?

In 2020 Gabriel Krauze published Who They Was. It was his first novel and it was longlisted for the Booker Prize – a powerful dispatch from a world rarely glimpsed by the literary establishment. Whether it was fiction or non-fiction didn’t matter. Not to some of us. Was it a memoir? Was it a work of imagination? Who gave a shit? The voice of Snoopz, the central protagonist, and those of his contemporaries, were unclouded by the conventions of literary form. This was the vernacular of London’s ends. 331 pages set in Bembo std. Issued by a legit publisher in novel form for the first time. I’m no literary critic, but I was excited when I read Who They Was. And so were many of my contemporaries. But was the mainstream literary world ready for a piece rendered with this much honesty?

‘What happened with Who They Was is the critics could not fucking understand the book. All the mainstream reviews and interviews focused on questioning the authenticity of the work. “Are you really an ex-gang member? Were you really committing these crimes? Are you really about that life?” It’s thrilling, it’s exciting for them, but not one of them ever engaged with the philosophy behind the book, with that view of morality being relative to the level of danger in which you live. Because they can’t package me, they can’t figure out how to place me. They never went beyond the sensationalist experience. Everything that happened in the book was real. The characters or what happened to them weren’t composites. But it remains a novel, a piece of art. The mainstream literary establishment in this country could not handle that.’

In the hot, locked-down summer of 2020, a few weeks before publication of Who They Was, I spent an afternoon with Gabriel Krauze in the South Kilburn block where much of the action in the book takes place. In the heat of the afternoon we sat toe-to-toe drinking water. There were questions around truth and fiction; authenticity and affectation; guilt and innocence; violence and masculinity. This was, remember, not only at the heart of lockdown, but also in the wake of the killing of George Floyd. In May of that year the violent reality of a murderous white cop’s knee in the back of a black man’s neck had (finally) outraged the world. Violence. Race. Truth. Reality. All these things were in question. Identitarian politics and the discourse of authenticity were clogging up your echo chamber. The world was in the thrall of an existential uncertainty amplified by the strictures of the pandemic. A paranoid digital miasma had begun to circulate the planet. You couldn’t believe what you saw. You couldn’t believe what you read. The old certainties had begun to evaporate. Here in 2024, that state has become ambient. And Gabriel Krauze’s second book is in the process of becoming.

‘The body of my work until I die will probably be dominated by the theme of masculinity and violence. I connect with this subject because I am a man who grew up amid violence. It’s the thing I am able to explore in a way that my contemporaries are incapable of exploring. The environment and culture in which I grew up doesn’t usually produce literary writers. I am a writer. I am who I am. And that’s why I produce the kind of work that I produce.’

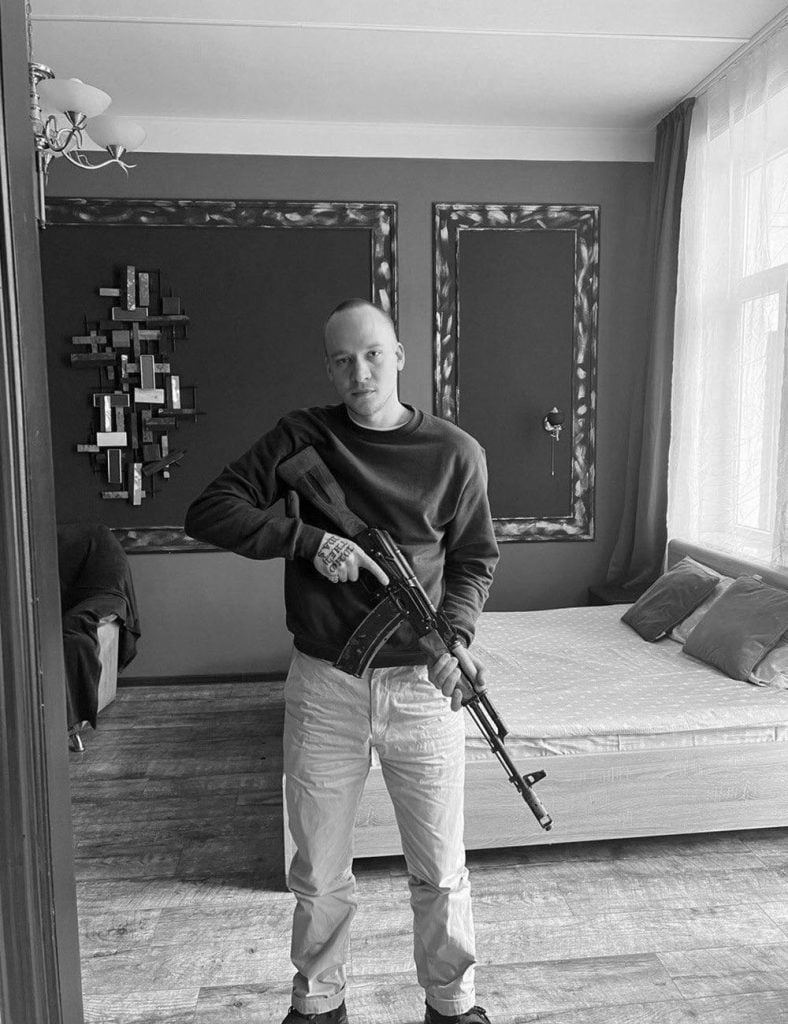

Who They Was was always going to be a hard sell for the mainstream. Covid restrictions meant the usual book tours and literary launches, that would have accompanied a major launch from a proper publisher, had been rendered more or less impossible. This was a book going deep into the details of violent crime in the blocks of London. Written by white man. A white man studying for a degree in literature at London’s Queen Mary University. Tricky territory. It shouldn’t be. But it was. And is. But whatever caused the book’s limp (near non-existent) mainstream reception, Gabriel Krauze pushed on. When we met again, in another part of London, a long way metaphorically and physically from South Kilburn, he was about to travel to Ukraine for the third time. The forthcoming book is set among young men there.

‘I want to just re-immerse myself in the feeling of being there. I don’t need more experiences. I don’t need to interview more people. I don’t need to see more things. I’m going to write the draft in situ, in my friend’s flat in Kyiv, although if more opportunities arise to go to the front I’ll probably take them. The book is called Agony in the Garden. It focuses on young men in Ukraine living on the edge, and it explores how a certain type of young man finds a certain freedom in the kind of danger that could ultimately cause their destruction.’

THE REAL DEAL

When I met Gabriel in South Killy it was already apparent. He was the real deal. There was an intensity about him. The kind of focus that you find in committed, high-level athletes and artists for whom the work is deeply ingrained in their being. Here in September 2024, that intensity has deepened. He still writes in a spartan room in a small council flat. He still writes in longhand in a series of tightly inscribed notebooks, only committing to the computer in later drafts. His writing room is decked in literature, mostly European, as well as artists’ monographs and philosophical treatises.

‘I have read widely around the British tradition as well as the European tradition and I am drawn perhaps to the literature of the extreme. But literature doesn’t have to be “extreme” to be great. Some of the greatest literature is simply about human relationships. For me, I think it’s about discovering a kind of existential truth by exploring people out there on the edge…’

Gabriel’s mum and dad, both creative souls, were born in Poland. We talked at length about the blood-soaked history of his parents’ homeland and how inherited experience is able to pass down through generations. It was perhaps inevitable then, that the writer, born and raised in London, would be drawn into exploring what is going on in Ukraine and among the young men who fight there.

‘There was something in Ukraine, where I saw a nation that hasn’t quite come into its own, and so it still has the potential, through great sacrifice, through great suffering, to reinvent itself, to renew itself, and then to create new and beautiful things. I’m not saying that war is a tonic, that we should all be taking part in war, or that war has a huge societal benefit. But In the West it feels like everything has become stagnant and self-indulgent and empty of meaning.’

Four years is a long time in terms of cultural history. America is devolving into dangerous polarity. Ukraine and Russia remain bound in a murderous deadlock motored by Iranian- and US-made drones and standoff weapons. And as I write the Israeli Defence Force is in the first day of its ground offensive in Lebanon, while Iranian ballistic missiles are falling on Israel. The time for addressing violence is here. But is writing about young men in the estates of London the same thing as writing about young men fighting in Ukraine?

‘There is something universal in the people I write about, whether they’re from South Kilburn or Ukraine. I would say Who They Was was about young men and violence. The second book is a lot more about suffering as an essential part of the human experience. The crossovers between somewhere like South Kilburn and Ukraine is this willingness to throw yourself into danger, to go head first into danger. You realise that this extreme experience will give you meaning in an existential sense, but also give your life potentially a meaning outside of yourself. Within gang culture there’s the obsession with reputation. Within the culture in Ukraine, among young men, it’s not so much about reputation, because they don’t need validation. Their validation exists among themselves, because they all decided to take up arms and go and fight.’

THE ESSENCE OF WAR

Storytellers have, of course, very often been drawn to explore the places where war is happening. Orwell in Spain. Hemingway on the Italian front and everywhere else. It is in places of conflict where the tectonic plates of history shift. That energy creates stories that are universally relevant. But these writers did not live in an age of YouTube. The intimacy with destruction that provided so much of the juice for an artistic fascination with war is now only a couple of clicks away. Real time is real. The web is awash with it. What then, is the relevance of literature in this context? Can good writing get any closer to the essence of war, and its motives, than the paper-thin prophylaxis of the screen?

‘There was a moment in Ukraine when I asked a soldier to take me to Zero, which is what they call the most far forward section of the front line. I wanted to write about it, I wanted to see it. But he refused. He told me that he was not going to take me there, because there are a lot of other guys other than me who could come and be good fighters in the trenches, but there weren’t a lot of guys who can write the way I write. The chance of me dying or being severely injured was too great for him to let me come, because my real value was in my ability to create art from this situation.’

TRUTH AND FICTION

If Who They Was caused controversy because of the apparent blurred line between truth and fiction – an ambiguity that the publishing industry and the media that surrounds it had trouble handling – then the piece Gabriel is writing in Ukraine is bound to cause similar ripples. Does an artist make concessions? Can you be prepared to flex as circumstances shift and the reality of making a living rears its head?

‘I don’t want Agony in the Garden to join the conveyor belt of non-fiction books about Ukraine. There’s going to be hundreds of books coming out by journalists, analysts, historians about the Ukraine war. But this will be a novel. The value of all these stories emerge when you turn them into literature, because literature transcends the basic experience and goes into something both universal and philosophically relevant. It has to have some kind of deep substance that relates to the human condition. So with this book the approach is even more complicated than Who They Was. I’m struggling to work out how to approach it. There’s no reason why here in the 21st century the novel cannot be a work of non-fiction. I want to be taken seriously as a writer and as an artist. There is artistic intention behind my writing. I build these works of art from the raw material of reality. I will state for the record everything in Who They Was really happened. But it is a novel. It is, and will always be, a work of literature. It will be the same for Agony in the Garden.’

Gabriel Krauze is made from strong stuff. The life he documented in Who They Was leaves traces on the individuals who experience it. Isn’t the author’s urge to get up close and personal with the realities of war an extension of this trace element? He has stated in detail to myself and others that his work is an attack on the culture of ‘trauma’ that afflicts the language and the culture of contemporary writing. But can you ignore the T-word? And what is the recurring and often fatal attraction to violence if not a manifestation of intergenerational trauma itself?

‘My agent presumed I was traumatised when I got back from Ukraine. But, and I’m not saying this in a macho way, I can just cope with this stuff. The biggest thing that I felt about war actually was how disgusting it is. I think any novel that writes truthfully about war is anti-war, because when you know what war is it’s absurd and it’s disgusting. When you see the men who’ve come back from Zero from fighting, they look transformed. They look dirty, exhausted, and haggard. They stink. Their language is brutal. But I can cope with it. Maybe there’ll be a point in my life when I’m exhausted by it. But for the moment, to write this book, I have to keep inserting myself into this until it’s written. When it’s done I’m going to have to go in search of pure beauty, somewhere like the Italian countryside… somewhere where it’s pure beauty.’

REALITY OF VIOLENCE

Gabriel reads me a section of the new book. I can’t quote it here. He reads with intensity in that voice. The paragraph he chooses is shot through with hard-edged imagery. But there is a beauty to the description. There is creative precision in the way he describes the frightful reality of violence. There is a tenderness in his descriptions of soldiers and the things they say. For him, these are men of thought, of understanding, of reflection – as well as violence. They are engaged in something that transcends their particular time in history. They are all actors in a drama that goes beyond their individual and collective experience.

‘I was long-listed for the Booker, having written a book intensely about the reality of London, yet I have never been invited to a book festival in England. But I don’t need this sort of validation to continue making my art. At a book festival in Australia, a very accomplished writer said to me that she felt that she was reading in my work something that had been smuggled out of a forbidden zone. I was humbled by that. She recognised what I was really trying to do.’

Words: Michael Fordham Photos: Michael Fordham, Gabriel Krauze

First published in Issue 3 of Bother Magazine, December 2024.

BOTHER is the HebTroCo print magazine.

The antidote to the algorithm with a coupon in every issue.

Buy the latest issue of BOTHER