The PinnacleA new book charts the early influence of British manufacturers on what has become the stratospheric outdoor clothing market.

You don’t need us to tell you that the outdoor clothing market is enormous. Folks who haven’t set foot on a muddy trail, never mind a snowy alp, are permanently bedecked in North Face, Arc’Teryx, Patagonia and the rest. The market is dominated by US behemoths, but a new book, Mountain Style: British Outdoor Clothing 1953-2000, describes the huge impact British companies had on the genesis of the industry. Co-authors Max Leonard and Henry Iddon put Britain’s place at the cutting edge of early developments down to imperial exploration, and its legacy.

(Left) The Fylde Mountaineering Club looking magnificent in the Lake District, some time in the 1960s.

(Right) An inspirational French Alpaca Duvet, 1953 Everest expedition.

‘British mountaineering and outdoors has always been important. Rightly or wrongly, we’ve always been pioneers of mountaineering, particularly alpinism, but also exploration and adventure,’ says Henry. ‘We’ve always gone out and explored. Everest in the 20s, when Mallory and Irvine went; Everest in ’53 [when Hillary and Tenzing were first to reach the summit as part of another British expedition, though neither were British]. All that’s tied into imperialism, in a sense. Then through the 60s and 70s we were one of the pioneering nations for fast and light alpinism.’

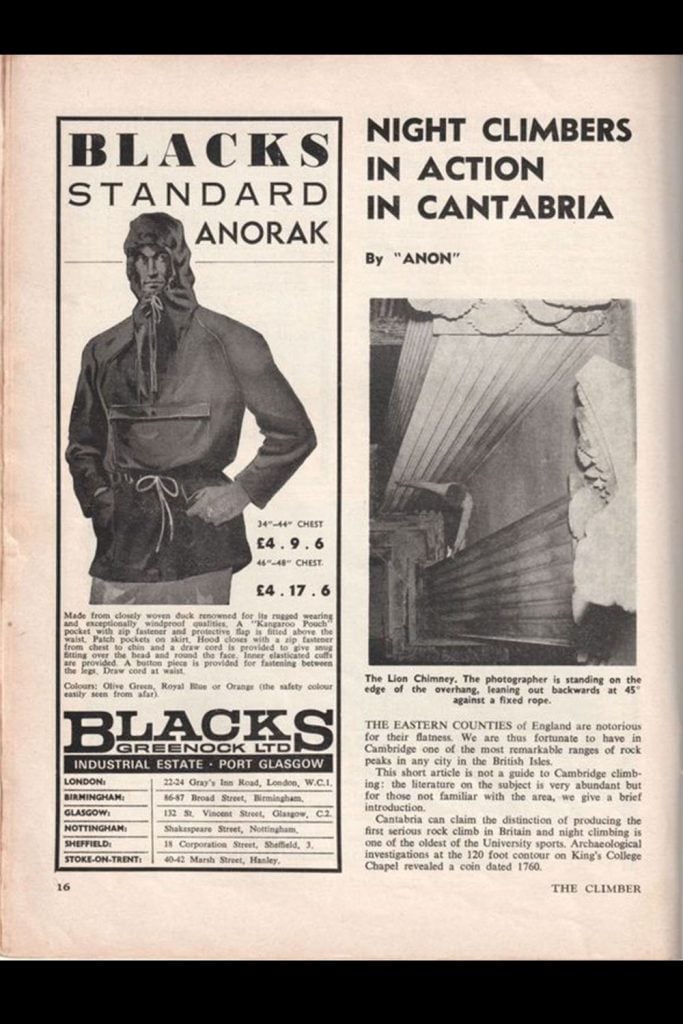

(Left) 1996 Black’s smock advert.

(Right) In 1953, on Snaefell.

Max adds, ‘The first down jackets date from the Everest expedition of 1922.’ He’s describing the British Mount Everest Expedition, that reached 8321m, just over 500m short of the summit. ‘But, that technology wasn’t really taken up in the UK. It developed on the continent, because I just don’t think we have the weather for down jackets. Now we have synthetic insulation that works much better in cold, damp places. The Everest smock that was worn was very cutting edge in that it was a nylon and cotton blend. Nylon was a very new technology.’

Textile Heritage

Because British expeditions were pushing the boundaries of mountaineering, it meant they needed better equipment and clothing. It helped that Britain had a textile industry and its residual know-how that the start-ups and innovators could lean on. ‘There’s definitely a need in our part of the world for gear that will keep you warm and dry,’ says Max.

Britain was still subject to rationing in 1953, the year in which the book’s content starts, but the successful summiting of Everest came shortly after the 1949 establishment of the UK’s national parks, and three years before the launch of the Duke of Edinburgh award, which placed value on youth-led expeditions and physical recreation, continuing the work started by Outward Bound. The DoE was primarily designed by John Hunt, the leader of the successful 1953 Everest expedition. Another significant factor leading to a boom in interest in the outdoors was improved transport access to the countryside.

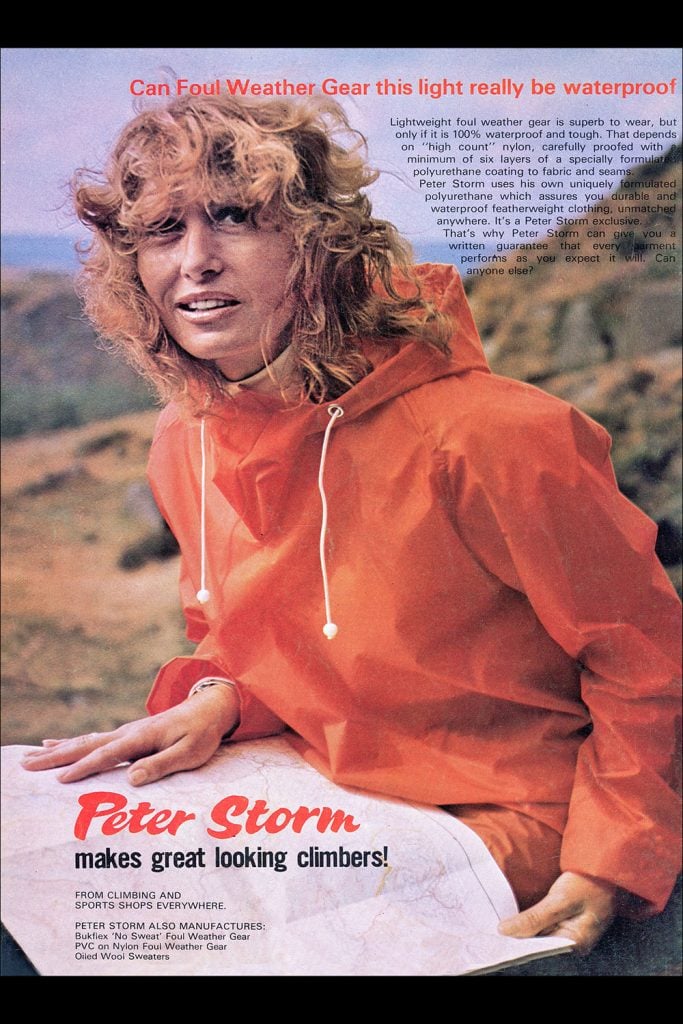

(Left) 90’s goofing.

(Right) Belstaff anorak.

Perfect Storm

From a consumer clothing perspective, the authors identify two points when garments crossed over from specialist mountaineer to weekend walker. Firstly, when Blacks introduced an over-the-head smock in the 1960s, and then when Peter Storm used the new ‘wonder fabric’, nylon, to create the cagoule.

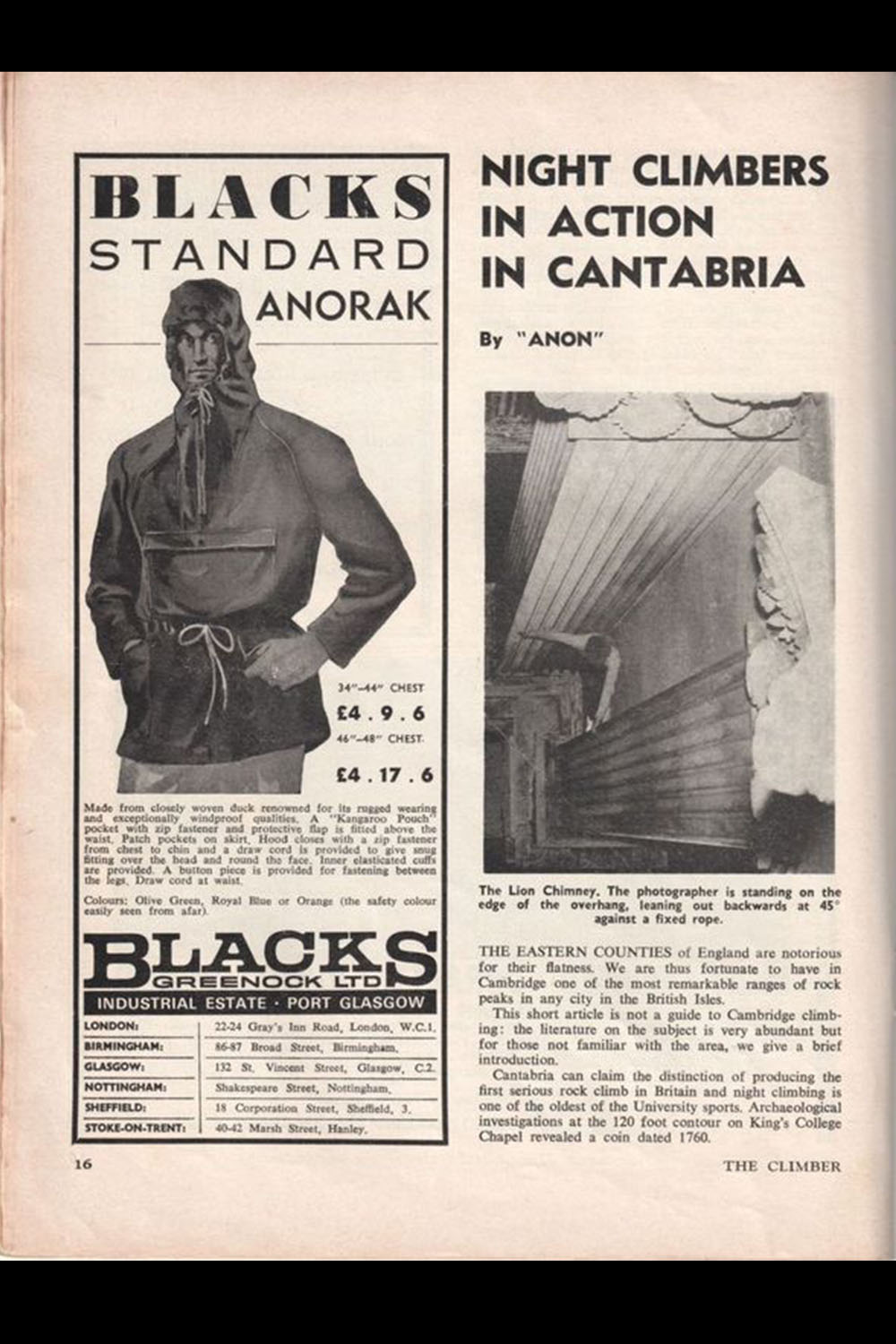

‘[The boom] was linked to changes in technology,’ says Max. ‘When someone was able to make a nylon jacket or anorak proofed with polyurethane, you suddenly, for the first time, had a very lightweight waterproof. That was a game changer. And Peter Storm seemed to be the first brand, as we would know it now, that made these garments and marketed them in a more modern way.’

Peter Storm ad shows changing times.

While Peter Storm was a boon for hikers, more adventurous climbers continued creating their own versions of the ideal specialist clothing.

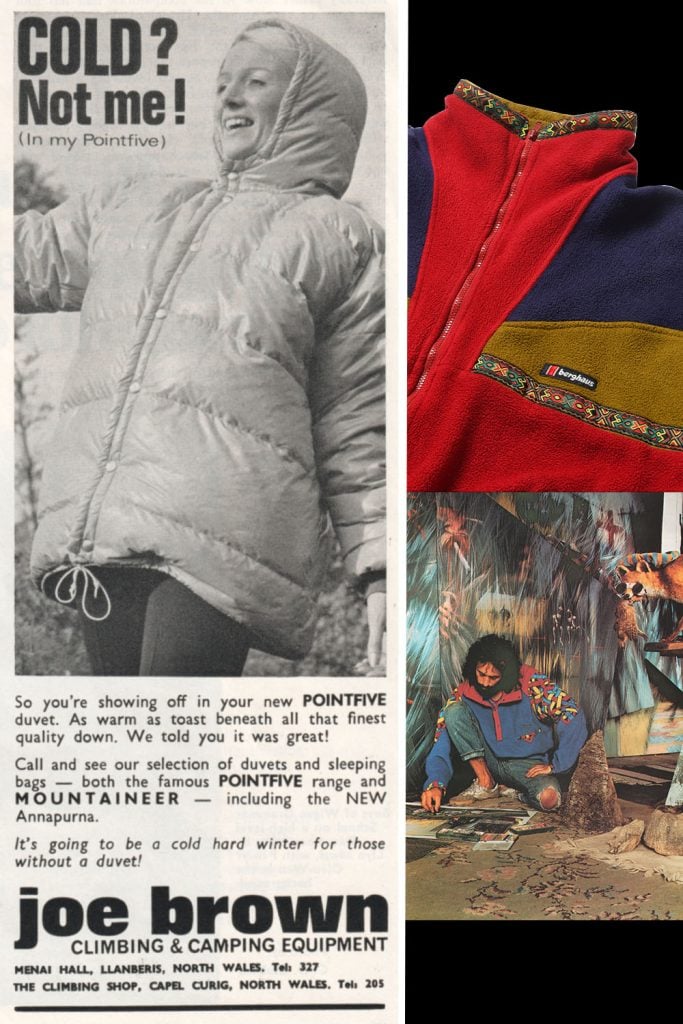

‘It’s what developed into the large companies that we know today. Mountain Equipment, which was very famous for down-insulated jackets, started in the early 60s. Berghaus started [as manufacturers] in the 1970s and were the first in Britain to use Gore-Tex. It’s the 70s when you start to get this idea of choice and some kind of style.’

Craghoppers joined the fray, then Sprayway, but then a name I didn’t expect to have such respect from these experts enters the conversation.

(Left) Red Point ad. (Middle) Craghoppers ad. (Right) Trousers from successful 1955 Himalayan expedition.

‘One of the brands that came along in the mid-to-late 70s that absolutely revolutionised things and upset the apple cart was Rohan,’ says Henry. ‘They used light polycotton fabrics and stylised designs, and they were quite brash and bold in their marketing approach. They placed full-page adverts in Sunday supplements. It was very modern in the sense of clean lines, and architectural, almost. Eames chairs in the shops and that sort of thing. Rohan switched it from being woolly jumpers and beardy blokes into a style element, even though they started making high-quality mountaineering wear for mountaineers at the pinnacle of the sport. Peter Habeler wore a Rohan jacket to the summit of Everest without supplementary oxygen in 1978, but they were still super stylish and revolutionary in the late 70s. They had catwalks at the outdoor trade shows. Nobody else was doing that. They really gave the industry a shake.’

It was a time when a small company could make a big leap, it was a dynamic period for the burgeoning technical clothing sector.

(Left) Troll stripy leggings pre-date the current obsession with skintight leisurewear.

(Top) Habeler in a blue Rohan Windlord. He and Messner, the first to summit Everest without Auxiliary Oxygen.

(Bottom) Original Berghaus Trango.

(Right) Troll 1980s

And… Breathe

‘Towards the end of the 70s, Rowan, in particular, started to make gender-specific garments,’ says Henry. ‘Because of Gore-Tex, you didn’t need bagginess, so things could start to become more tailored.’

The breathability of Gore-Tex, compared to coated nylon, meant the experience wasn’t quite like yomping in a crisp packet, so there didn’t need to be so much room to allow the body to breathe.

So, where did it go wrong for these trailblazers, to the point that even the biggest British companies are like moons orbiting the American giants?

(Left) Advertising through the years.

(Top Right) Berghaus fleece.

(Bottom Right) John Redhead absorbed in his studio.

I don’t think things did go wrong, but the American companies have a huge domestic market which makes them incredibly powerful and wealthy,’ says Max. ‘And if you think of Patagonia or North Face, you think of cool pictures of people hanging out in Yosemite, and the 70s hippie thing, which they export very successfully. But that’s on the back of hundreds of millions of people in their domestic market, and an outdoor culture that’s also much bigger.’

Patagonia founder and the outdoors world’s Yoda, Yvon Chouinard, started out selling stuff from Yorkshire-based Ultimate Equipment, Umbro rugby shirts and Craghopper britches he imported from Britain.

(Left) Want to look cool? Wear man-made fabrics!

(Right) Berghaus Chris Bonington expedition coat. Yes, please.

When talking about the creation of the book itself, Henry says, ‘It’s been monumental, bigger than either of us thought. The amount of research that we’ve gone into is enormous. I went through magazines from 1964 till December 1999, trawling for information, gear, reviews, pieces about clothing… We were keen to get good-quality images from the 70s and 80s, but it has been incredibly difficult to find them.’

But it was worth it. Max concludes, ‘To be able to chart the rise of these companies, that were created by very maverick, pioneering, anti-establishment mountaineers, in a shed on a farm near Hyde in Manchester, for example, where Mountain Equipment started, or Rab, [founded by Rab Carrington]who started his company in his attic in Sheffield. Hearing the story of the start of these things is always interesting.’

Words: Gary Inman Photos: Courtesy of Isola Press

First published in Issue 3 of Bother Magazine, December 2024.

BOTHER is the HebTroCo print magazine.

The antidote to the algorithm with a coupon in every issue.

Buy the latest issue of BOTHER