Teddy BoyHow a chance moment in an attic lit a blazing flame of rock'n'roll obsession for a late 70's teenager

‘You might as well put a bloody big target on yer back!’

It’s spring 1980, I’m 15 years old and standing in the living room at home, a three-bed semi on the northern fringes of the English Black Country. The comments of doom are coming from my dad.

‘Bloody ridiculous. You’re asking for trouble.’

I barely register his bellyaching. I’m in a state of ecstasy.

Let’s go back a bit, to autumn 1977, coming up to my 13th birthday. I was now tall enough to stand on the bannister at the top of the stairs to reach the loft hatch. Just as importantly, I was strong enough to pull myself up through the hatch. It was maybe the second or third time I’d done this, exploring dusty boxes by the light of a dangling 40-watt bulb. This time, treading carefully on the joists, I went to the back wall. The first boxes there turned up old crockery, books, my dad’s old fishing tackle… But then I found two boxes of records. One held loads of 78s of dance bands, labelled such as ‘foxtrot’ and ‘quickstep’. I closed it. The other was full of 45s. I took it downstairs.

At that point, I hadn’t been truly hooked by music. Certain stuff on the radio might catch my ear, but I hadn’t got into anything in particular. Punk was in its pomp, but I was too young for it, too soft. I had four albums: Great TV Western Themes, The Planets by Holst, Winnie the Pooh and the sound track of Disney’s The Jungle Book, all stuff I’d had since before the age of ten. My obsession, apart from masturbation, was motorcycles, especially British marques such as Norton, Triumph and BSA, and I spent hours drawing their logos in biro. But music, well, you know… It was OK. Then that box of 45s blew everything wide open.

That afternoon, I had the house to myself. I sat on the floor in front of the record player, fished a record from the box, slid it out of its paper sleeve, lowered the needle and gave it ten seconds or so. It didn’t grab me. Next! This went on for quite a few, by the likes of Kathy Kirby, Jim Reeves, Acker Bilk… But then something looked promising. I liked the black and silver label of exotic-sounding London American Recordings. The band was Johnny and the Hurricanes and the track Red River Rock, released in 1959. I reckoned it wouldn’t be a soppy crooner or some bearded old boy fingering his clarinet. I wasn’t wrong. It was, I’d go on to learn, late-era rock’n’roll.

I lowered the needle and after a few seconds the crackles and pops were drowned by guitars and drums. To say I immediately wanted to slash the settee and put my foot through the living room door would be an exaggeration, but not by much. I turned the stereogram up full and immersed myself in a surge of energy and excitement that pretty much doubled when I flipped the record over and heard Buckeye on the B-side, all honking sax, snare-drum cracks and driving guitars. That was it. By the end of the afternoon I’d turned up maybe ten more singles that hit the spot, by the likes of Buddy Holly, Duane Eddy, Del Shannon, and The Shadows. I’d been branded on the arse by a searing sound that would leave me marked for life. The floodgates were about to open.

Hair Apparent

The next day, I shared my discovery with a couple of mates, Smiffy and Thack, who ransacked their parents’ and elder siblings’ record collections and turned up gems by such as the Ramrods and Little Richard. Just as significantly, Thack showed us photos from his family album of his dad in the 50s, with greased-back hair, quiff hanging down. This being the late 70s, the three of us had hair over our ears and well over our collars. We all decided to get our hair cut in what Thack’s dad told us was often called a Tony Curtis, with a DA, or duck’s arse, at the back, where the hair combed back from the sides comes together to form a vertical valley. Funnily enough, we all went to different barbers. The one I went to spent the whole time telling me how stupid I’d look, but I didn’t give a shit and felt a buzz of adrenaline as a rough approximation of what I wanted appeared in the mirror. It wasn’t great, but I’d taken the plunge. Teddy boy stage one.

The smell of Brylcreem, or anything reminiscent of it, takes me straight back to standing in front of the big mirror in the hall at home, obsessively combing, re-combing, teasing, twisting… trying to get my naturally wavy hair to comply. The stiff styling gels available now weren’t around, certainly not where I lived, so grease it was. Plenty of it. Later, I discovered the stickier Tru-gel in a tube, but it was pricey stuff.

At this point, our casual clothes hadn’t changed from denim jackets and flared jeans, and at school we had a uniform. In fact, school became a challenge. We were still only 13 and the only kids in the 1500-strong comprehensive combing back their hair. We stood out like greasy thumbs to the bigger, harder kids, many of which were mods, skins or punks. But with that haircut comes a certain attitude and swagger, and none of us had ever been in the habit of backing down easily. We learned to survive.

With the hair tamed, or at least a work in progress, we started trying to replicate a 50s look. The early to mid-70s had seen various teddy boy revivals, and daft bands like Mud and Showaddywaddy on the fringes of glam rock wore drape jackets. Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood had opened their King’s Road shop Let It Rock in 1971, where the teddy boy look was championed and, later, creepers were adopted by punks, which meant they were available. It’s thanks to all these things that getting a handle on the style was achievable, even for a bunch of kids in the West Midlands. Thanks also to the film That’ll Be The Day, with David Essex, in which Ringo Starr’s character was a ted. My step sister had the double album of the soundtrack, with useful photos on the gatefold sleeve, and which also provided a load of original 50s rock’n’roll.

Gearing Up

We began assembling the gear piecemeal, restricted by lack of money. We found a shop in Walsall, M&J Fashions, which sold straight-leg trousers and for a couple of quid extra would take them in to create even tighter ‘drainpipes’. This was a mild form of tailoring and brought us closer to the original teds, those working-class lads of the mid-50s who’d get their drapes made, or tweaked, to their own designs. But drapes were out of our reach.

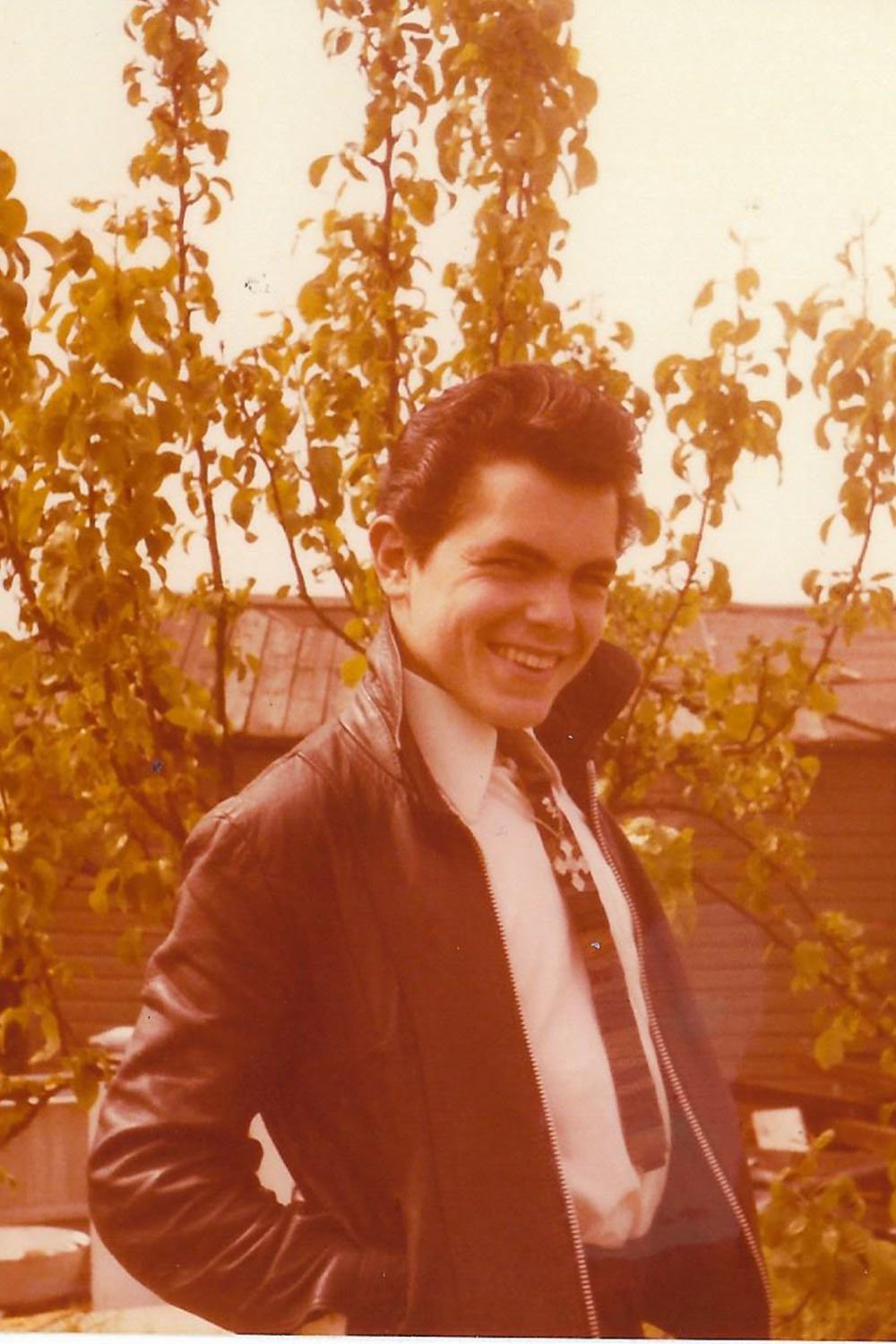

Creepers, on the other hand, were available in those huge mail-order catalogues that your next-door neighbour or auntie was an agent for. Now aged 14, I ordered a pair in blue suede, with apron fronts and D-ring lacing. The day they arrived, I pressed my drains and a white shirt, put on a skinny Tootal ‘Young Blade’ tie that Thack had snaffled from his dad, added a skull-and-crossbones tie pin and hung a sort of Bottony cross pendant over the top of the tie. I don’t know why, it just felt right. With the creepers on, the outfit was finished off with a black leather bomber jacket my parents had bought me the previous Christmas.

We’d parade around Walsall in our cobbled-together look, breezing into record shops to hunt out original rock’n’roll or rockabilly on rereleases or compilations. One of the first albums I bought was Buddy Holly’s Greatest Hits on the budget Music For Pleasure label. That cemented a love of Holly that remains to this day. We were too green to think of seeking out second-hand record shops, probably in Birmingham, which would have had cheap 1950s singles. Instead, the Walsall branches of WHSmith, John Menzies, Boots and one or two independent record shops, such as Sundown, were our saviours. Teenage semi-teds hunched over the record racks in Smith’s must have a been a bizarre sight.

We weren’t proper teds without that essential tribal adornment, the drape jacket. For me, the revelation was a small-ad in the back of a mate’s copy of NME. Drape jackets, mail-order, off the peg, in a choice of three colours – pillar box red, royal blue or charcoal grey – all with black velvet trim. Thirty quid. Just doable with money saved from a pound-an-hour Saturday job. I sent off… and waited.

By now there were eight or nine of us at school who were all greasing our hair, and it seemed like at least five of us got our drapes at about the same time. The day mine arrived, I ran up to my bedroom and started the primping and preening. The M&J drains; brightest shocking pink socks; black shirt with button-down collar; slim, sky-blue tie; belt with big buckle depicting an American Indian in full headdress (what else?), and those blue suede creepers. Then downstairs to the big mirror in the hall so I could watch myself slip on my royal blue sensation. There followed a long spell of self admiration, caressing of velvet and hair combing. I couldn’t wait to make my entrance at The Rock Box, a monthly rock’n’roll night at the glamorous Aldridge community centre. But before that…

I strode into the living room. Mum and Dad were watching telly. Here’s where this story started. My dad’s derision was probably typical of a bloke born in the 1920s, for whom Glenn Miller was a hero, not Eddie Cochran. Teds got a bad press in the 1950s and many people remembered them only as gang-forming troublemakers. I loved to think of myself as a gang-forming troublemaker, but my first outing in that new drape was into the back garden for my mum to take some photos. Yeah! Rock’n’roll!

By late 1981, my beloved DA was growing out and the drape stayed in the wardrobe. It’d been a great ride of three years or so, a fair chunk of time for a youngster, and, despite my dad’s dire warnings, we never did attract much trouble. The look was supplanted by bike jacket, boots and long hair, but the love of the music and that sartorial splendour never died. Once a ted…

THE ORIGINS

Ted roots go back to the 1940s

Teddy boys and rock ’n’ roll are joined at the hip, but it wasn’t always so. The look is a revival of a revival, morphing each time into something which retains its roots, but with marked detail changes.

The original fashion was popular in the English Edwardian period of the first decade of the 20th century, hence ‘Ted’. It was first revived by Savile Row tailors in the late 1940s, offering a lavish style that used plenty of cloth in an austere post-war Britain. It was taken up by the affluent elite, in particular off-duty or former Guardsmen and Oxbridge undergraduates.

The style was soon adopted by working-class London lads, meaning wealthier clients dropped it like a hot turd. Crepe-soled shoes started to replace Oxford toe-caps, and cowboy films brought in Wild West elements, such as the maverick tie. The 1970s revivals popularised drapes in lurid colours. So the look pre-dates rock ’n’ roll’s mid-50s birth, and those early teds would have listened to jump, jive, R&B and skiffle, though they lapped up rock ’n’ roll when it arrived.

Words Mick Phillips Photos Phillips Family Archive

First published in Issue 4 of BOTHER magazine February 2025