Like drawing but louder, brighter AND hotterDan Rawlings is the kid who used to fix his mates’ jeans and hang around the bicycle shop, borrowing tools. Matt Letch knew he’d become something, but what?

When Dan Rawlings was a teenager he was part of the local BMX and skate scene that hung out in and around the Essex bicycle shop I owned at the time. Even then he had something special about him. I always thought his name alone deserved a BMX pro contract. He always worked on his own bikes and, in hindsight, only really came into the shop when he didn’t have the specific tools he needed. I could tell he would become someone, I just didn’t know how or what?

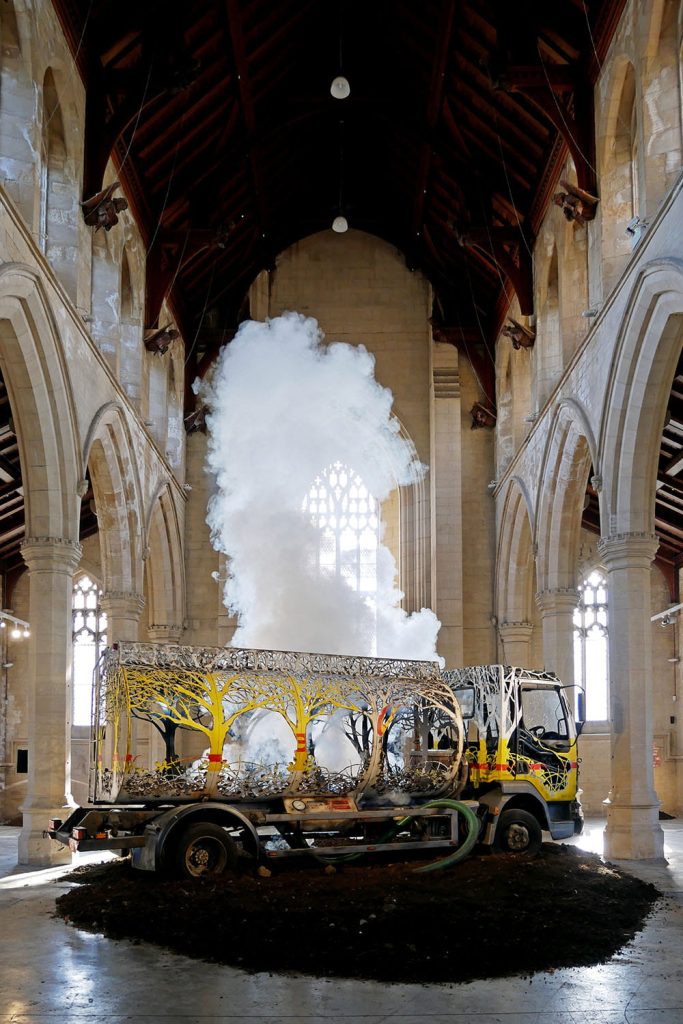

Since our paths diverged, Dan has navigated a route through screen printing, concert rigging, graffiti and organic farming in Cornwall, before becoming an artist who has exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery, and has had an artfully chopped-up oil tanker on display inside Lincolnshire church, among other exhibitions here and abroad. He’s a true Renaissance man in a time of uniformity.

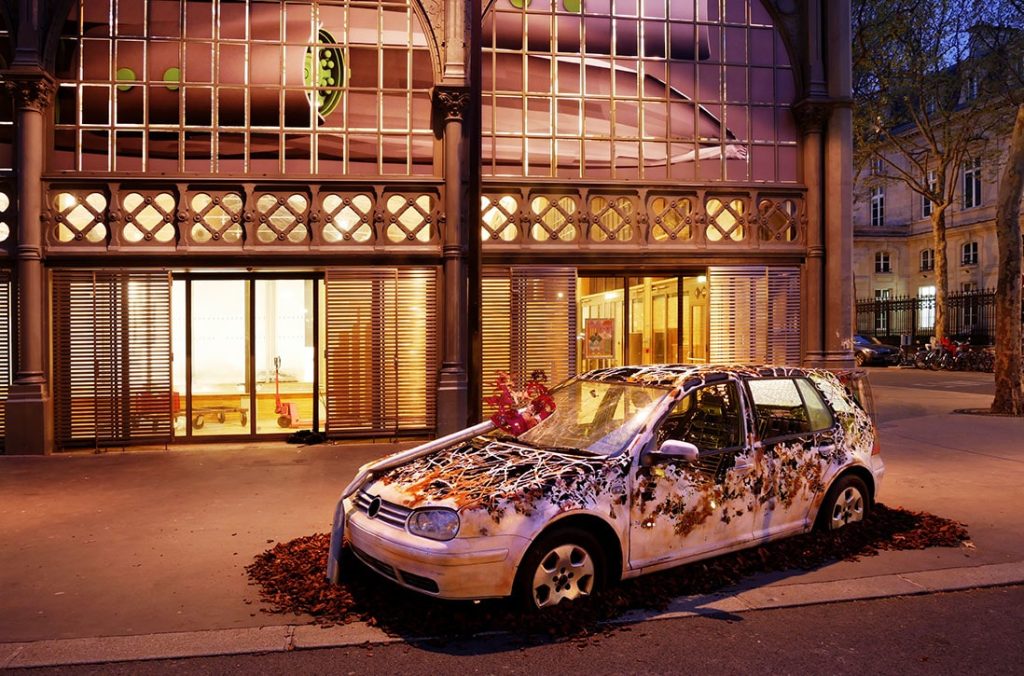

Today, Dan transforms industrial detritus into poignant sculptures that blur the line between decay and renewal. His works, crafted mostly from weathered road signs, rusted oil cans and, occasionally, jet-refuelling lorries, are both beautiful and haunting and feel like a warning, perhaps of future apocalypse, like something you might find on the edge of the road in a Cormac McCarthy story. They are also stunning, often casting shadows even more mesmerising than the pieces themselves, while also giving some of us hope that nature will win in the end.

A master of plasma cutting and vibrant painting, Dan creates intricate pieces hinting that the threatened ecosystem will reclaim what humanity has abandoned. With a solo exhibition set for Paris this March, his message of environmental reflection seems particularly prescient with the rise of the oligarchy and climate change deniers.

Art And Imagery

Dan was moulded in the best possible way by his childhood. He’s the spawn of a creative, resourceful family, what with his dad working as a film cameraman, and his mum’s love of textiles, he lived in a home rich in art and imagery. It was also a household that believed in make and mend, fix and repair.

‘If something broke, it was up to my dad to fix it,’ says Dan. ‘Every holiday we went on, the car broke down. Quite literally, there was always a day in the lay-by fixing something. We weren’t the type of family to buy new cars. We were super DIY. If you didn’t have it, you made it. If it was ripped, you fixed it.’

Not naturally good at school, he remembers himself as ‘a chaotic kid’. He was drawn to the outdoors, building dens in the woods with friends, where they’d stash kettles and sleep out at night, and to riding bikes. He thinks they kept him out of trouble. Even back then, his combination of practical skills and artistic ability shone through. His mum had shown him how to sew, and he became known for repairing torn jeans in his crew.

‘I’d patch people’s jeans, most often the right leg where it had gone into the chainring. I did it in a funny way, so they always looked cool. I just became the go-to seamstress. I love fixing things, finding stuff that’s kind of crappy and making it cool.’

Subway Sect

At the same time, a fascination for graffiti was growing, chiming with his ‘make it yourself’ approach to most things. Finding the book Subway Art by Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant, was one of those life-changing moments.

‘It’s an incredible book from the late 80s, the bible of graffiti,’ Dan explains. ‘Martha and Henry were New York photographers who got obsessed with graffiti when no one else was paying attention. They shot photos of trains painted by legends like Dondi, and the whole graffiti scene. Anyone involved in street art now knows this book.’

Dan became immersed in graffiti culture, and would make detours on his way home from school to visit a local graffiti hotspot, the old gas works in Chelmsford, Essex. ‘I’d go at least once or twice a week to see what had been painted. It became a part of my life.’

The path from graffiti to Dan’s plasma-cut sculptures started with stencils and screen printing. The layering, the precision, the almost alchemical transformation of simple materials into bold, evocative images fascinated him. ‘I got pretty obsessed,’ he admits. ‘It wasn’t just about the end result; it was about the whole process.’

After renting a workshop, Dan’s growing passion for screen printing led to making T-shirts and posters. He started with band merch and his own designs, selling online and at markets. But the T-shirts came with issues. ‘The Plastisol ink was horrible, it felt wrong to me. I wasn’t an amazing screen printer either, so I started gravitating towards posters. They felt more honest, more expressive.’

But by then he had fallen in love with stencils. A love of artists like the American Logan Hicks, who uses many, multi-layered stencils to produce his work, set a high bar and encouraged Dan to experiment with tone, texture and complexity. ‘Logan’s work is incredible. He can produce these intricate, fine-art-level images with stencils, using layer after layer of colour and tone. Mind-blowing.’

Brighton Rocked

Stencil art also appealed to Dan’s punk rock, DIY background. It offered the ability to quickly produce something and stick it wherever you wanted for the world to see. He was further spurred on by the experience of living in Brighton when both Banksy and Pablo Fiasco were at large in the city. ‘I used to make tons of posters, and just wet-pasted them

everywhere. I’d head out at night with a bucket, a roller and a stack of posters in a plastic bag. I loved seeing them around town over the next few weeks, hearing people talk about them and knowing I’d put them there.’ And hardly anyone knew what Dan was up to. ‘I was pretty shy, especially about creative stuff. But it all came together, I just loved cutting stencils. I’ve got folders full of them, and sometimes I like the stencils more than the stuff I made with them.’

As Dan’s art developed, it became a response to the world around him. Growing up in a household where DIY and resourcefulness were second nature, it’s no surprise that his sculptures tackle themes of reclamation and renewal. But his connection to environmental issues runs deeper, rooted in personal experiences and pivotal direct action.

Reading Naomi Klein’s No Logo, the 1999 book that warned a generation about increasing globalisation, was a lightbulb moment. ‘There’s a line that really stuck with me: “The Earth isn’t dying, it’s being killed. And the people doing it have names and addresses.”Seeing that in print hit me like a ton of bricks.’

Dan was impacted by the Newbury Bypass protests of the 90s. ‘It was one of those moments where you realise how fragile things are,’ he says. ‘You’re standing there, watching trees that have stood for centuries being ripped apart for a road. It felt personal.’

It makes perfect sense that his use of reclaimed materials often includes such as road signs and things associated with the oil industry.

Most of Dan’s current work is made using a plasma torch, a method he developed while doing something far more practical, which seems apt. It started with a Citroën van he found really cheap. He’d always wanted one. One day, elbow-deep in welding and patching, his workshop neighbour, Dwayne, turned up with an unfamiliar piece of equipment. ‘Here, try this,’ said Dwayne, offering the plasma cutter. Until then, Dan had been using a jigsaw, trying to coax intricate cuts out of sheet metal ‘The plasma cutter felt like a scalpel,’ Dan says. ‘A slow, precise scalpel that could slice through metal like butter.’

If you were to pass Dan’s workshop while he’s plasma cutting by hand, it would be easy to mistake it for welding. There’s the noise of high-amp electrical heat, blinding sparks, and a welding mask. Imagine a tiny bolt of lightning arcing between the handheld torch and the metal workpiece.

At first, Dan practised by cutting random shapes and freehand letters, playing, having a go. ‘It was more for the process than the result,’ he says. ‘I loved the immediacy of it, the way it felt like drawing, but louder, brighter, and hotter.’

You get the feeling when talking to Dan that his journey to being the artist he is now was accidental, this happened here, that happened there, but that reflects his personality and lack of ego. I knew when I first met him all those years ago he’d make something of himself, I just didn’t know what. My guess of a pro BMX career was off, but the talent, drive and the X factor he possessed were clear.

‘I’ve got so many things I want to make,’ he says when we discuss the short-term future. ‘Some of them I don’t even know how to make yet. Holly, my partner, is really into ceramics, and that’s spread to me. It’s such an enjoyable thing to do.’

A new skill to learn, something to practise… sounds familiar.

Dan has work in a group show called Flowers at the Saatchi Gallery, London, which opened in February. Currently, the best place to buy his work is at galleries. Chenus Longhi and Stolenspace in London both have work for sale.

Words by Matt Letch

Photos by Dan Rawlings Archive

First published in Issue 4 of BOTHER magazine February 2025