We're proud to partner up with the charity Curlew Action. They asked if we could make some funky socks, to raise money for the awareness raising and hands-on conservation work that they do. Together we’re aiming to save the UK’s largest wading bird, which is now on the conservation red list.

The Bird with No Storyby Mary Colwell

Every day we tell stories about British manufacture, traditional weaving techniques and the backstory to the clothes we make. How can we appreciate value without knowing the story? This is true for everything.

This week’s Bothering is written by our friend Mary Colwell who wrote about rewilding in issue 1 of BOTHER mag. She is the chair of Curlew Action a charity that we’re proud to support. Curlews mark the start of spring here in Calderdale when they arrive to pair up and nest on our moors. They are also on the red list of endangered birds. Mary’s story is full of hope as well as tragedy…

Words by Mary Colwell

On 10 October 2025 the Slender-billed Curlew was declared extinct by the IUCN. It still feels raw to say the deadening finality of that word, extinct. This delicate, long-billed wader, once a part of the wildlife community of Asia/Africa/Europe has gone.

A life once woven through ours

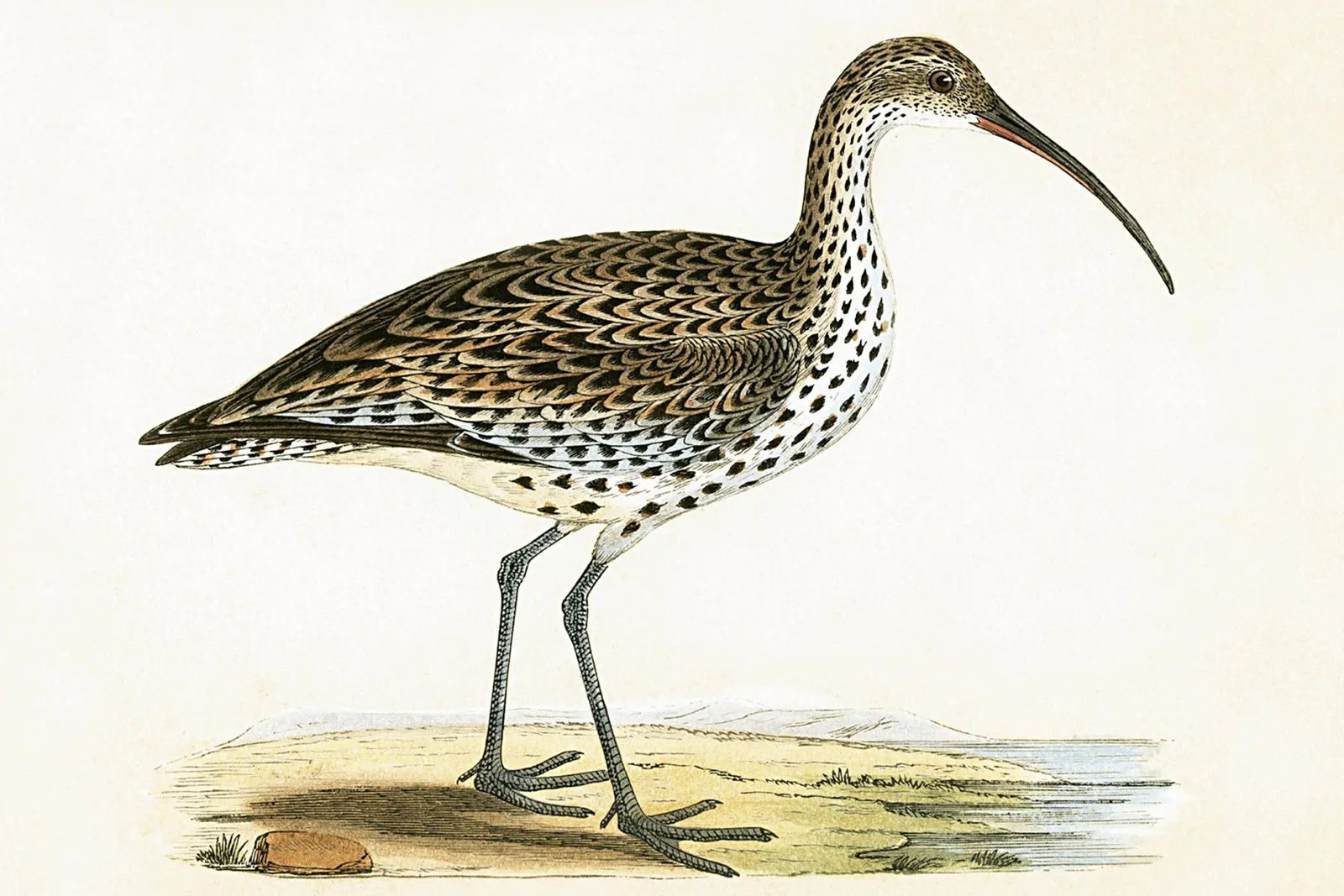

The Slender-billed Curlew lived alongside us for millennia, an unassuming yet glimmering thread in the weave of life itself. Nineteenth-century artists such as Alexander Francis Lydon and John Gould captured its grace and poise. It also had a tremulous voice; an airy, almost ethereal song that floated over the steppes and wetlands of Russia and Kazakhstan along the rocky coasts.

Slender-billed Curlew by John Gould

Thank goodness that voice was recorded. We can still hear it through speakers, even if it no longer brings a lightness and musicality to those landscapes. We also have a description of seeing it doing what it evolved to do, nest in peace.

“Slowly the sunset was fading, the curlews calmed down; the females sat on nests and the males landed nearby… The quiet, warm, spring night began.” - Ushakov, 1924

Those words transport us to a lost age and to lost landscapes which have now been drained, ploughed and converted to agriculture.

Slender-billed Curlew by Alexander Francis Lydon

Who was the Slender-billed Curlew?

It bred on the steppes and peat bogs of central Eurasia, nesting on grassy hummocks before migrating west to winter along the Mediterranean and in North Africa. Bree wrote in 1875 that “in Sicily and in Malta it is the most common species in that season.”

It was also common in butchers’ shops; hanging in shop windows. Undoubtedly, unsustainable hunting, coupled with loss of breeding grounds, began its long decline.

The final photographs

Above: Eurasian Curlew (R) and Slender-billed Curlew (L) by Richard Porter

In the 1980s, ornithologist Richard Porter captured a haunting image in Yemen, an Eurasian Curlew in front of its smaller, finer relative, the Slender-billed. The comparison is heartbreaking now; the smaller, more delicate Curlew is set-back, away from the crowd, staring out to an uncertain future.

The last confirmed photograph was taken in 1995 in Morocco by Chris Gomersall. By 2002 British Birds knew the writing was on the wall and warned that without “greatly increased efforts” the species was heading inexorably for extinction. And here we are.

Above: The last known photo of a Slender-billed Curlew by Chris Gomersall

The bird with no story

Why did we let it go? We had policy, we had data, we had warnings from scientists, birdwatchers and hunters, yet it still slipped into oblivion. I believe it was because we didn’t tell its story. If only an inner circle of scientists, ecologists and legislators know, it is not enough. The wider world must care, and to care it must know. We have to tell the story of wildlife so that complex ecological issues are made real and understandable.

Humans are story-makers and story-tellers. From cave art to Netflix, from the Iliad to social media, we understand the world through narrative, image and sound. Everything we truly value becomes meaningful when woven into story. A photograph of a polar bear on melting ice tells us more about climate change than any graph. Footage of an orangutan fighting off a bulldozer that is destroying its home conveys the tragedy of deforestation more powerfully than statistics ever can. The most successful conservation campaign in history was largely due to images of small boats trying to protect whales from enormous ships and harpoons. An ecological David and Goliath.

Greenpeace ship MY Esperanza and activists try to hinder the shooting of a minke whale by the Yushin Maru No.2 catcher ship. Photograph: Kate Davison/Greenpeace

The Slender-billed Curlew had everything a story needs; aching vulnerability, beauty for beauty’s sake, mystery in a world of certainties, and peril in the face of huge, existential threats, but no one told it to the world. No books, no popular press, no documentaries, no Tweets, no reels, no local story tellers, no global presence at all. Without a story, this tiny David fell before the modern Goliaths of progress, disconnect and indifference.

Lessons from other curlews

Nine curlew species once graced the Earth. Now one is confirmed extinct, the Slender-billed, and another, the Eskimo Curlew, is almost certainly gone and there have been no confirmed sightings since the 1960s. The rest, including the Eurasian Curlew, are in varying degrees of trouble.

The Eskimo Curlew was once among the most numerous water birds in the Americas. In 1860 Alpheus Spring described a migrating flock “a mile long… four or five thousand strong… their notes like wind in the ropes of a thousand-ton vessel.” Abundance was no protection for the Passenger Pigeon, and it wasn’t for the Eskimo Curlew.

Above: Eskimo Curlew by John James Audubon

Today the Far Eastern Curlew is Endangered, down 80 % in forty years. The Eurasian Curlew has lost half its UK breeding population in two decades. Ireland has lost 98 % since the 1990s. Only 98 breeding pairs remain.A grainy 2023 photograph taken in Country Kerry by Barry O’Donoghue from NPWS shows one of Ireland’s last curlews, a ghost on a telescope lens. That bird has now gone. We are seeing a repeat of the Slender-bills’ fate, a gradual dissolving, nest by nest, roost site by roost site; it is death by a thousand cuts.

Above: Curlew in Ireland by Barry O’Donoghue

Finding hope in story

To try to turn this tide, we must keep the curlews in the light. That’s why I founded World Curlew Day in 2018, a global celebration of art, poetry and song inspired by these birds. This year’s winning poem, The Last Slender-billed Curlew by Emma Price, is read by singer-songwriter David Gray. It is haunting, questioning; riven through with sadness.

In our technical, rule-bound, transactional, post-truth world, we sometimes forget that we are emotional beings. Giving people space to express love, wonder and grief for the living world is vital and increasingly important. Children’s drawings sent to Curlew Action from Poland and the United States are moving reminders that the next generation wants to care, if we give them the knowledge and permission to do so.

Teaching the next generation

For fourteen years I have campaigned for Natural History to be taught in schools in England, and soon a GCSE (an examination taken by 16-year-olds) will make that a reality. Natural History will be at the heart of schools. Education, legislation and empathy must work together. Laws set the framework; education and story ignite the will to act. It is too late for the Slender-billed Curlew, but not for the Eurasian, the Sociable Lapwing, the Northern Bald Ibis or the White-headed Duck, or for any other species on the red-list of doom that seems to extend year on year.

If we learn anything from the loss of the Slender-billed Curlew, let it be this: never again should a species vanish because no one told its story. Let’s be determined to let people-power be the fuel that propels legislation into action and for love and respect to keep it alive.

The Senegalese ecologist, Baba Dioum, wrote these words in 1968. They are as pertinent now as then, I believe even more so.

“We will only protect what we love,

we will only love what we understand,

and we will only understand what we are taught.”

This article was original published on the Curlew Action website. Words by Mary Colwell, Director of Curlew Action.